Filipino scientists have raised a fresh environmental concern after detecting a radioactive “fingerprint” in the West Philippine Sea (WPS), the portion of the South China Sea within the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone.

In a recent study published in the Marine Pollution Bulletin, researchers from the University of the Philippines Marine Science Institute (UP MSI), the Department of Science and Technology–Philippine Nuclear Research Institute (DOST-PNRI), and the University of Tokyo analyzed 119 surface seawater samples collected from various Philippine marine regions, including the WPS, Philippine Rise, and Sulu Sea.

The team identified elevated levels of iodine-129 (¹²⁹I), a long-lived radioactive isotope produced exclusively as a byproduct of human nuclear activities such as nuclear weapons testing, nuclear fuel reprocessing, and reactor accidents. Concentrations in the WPS ranged from 6.54 to 14.8 × 10⁶ atoms per kilogram of seawater—approximately 1.5 to 1.7 times higher (50–70% greater) than levels recorded in other Philippine waters. These elevated readings were statistically significant and suggest an ongoing or increasing trend compared to earlier observations in regional corals and seawater.

Iodine-129 is not naturally abundant in significant quantities; its presence serves as a reliable tracer or “fingerprint” of anthropogenic nuclear activity. Notably, the Philippines has no active nuclear power plants, no nuclear weapons program, and no direct local sources of such contamination, ruling out domestic origins.

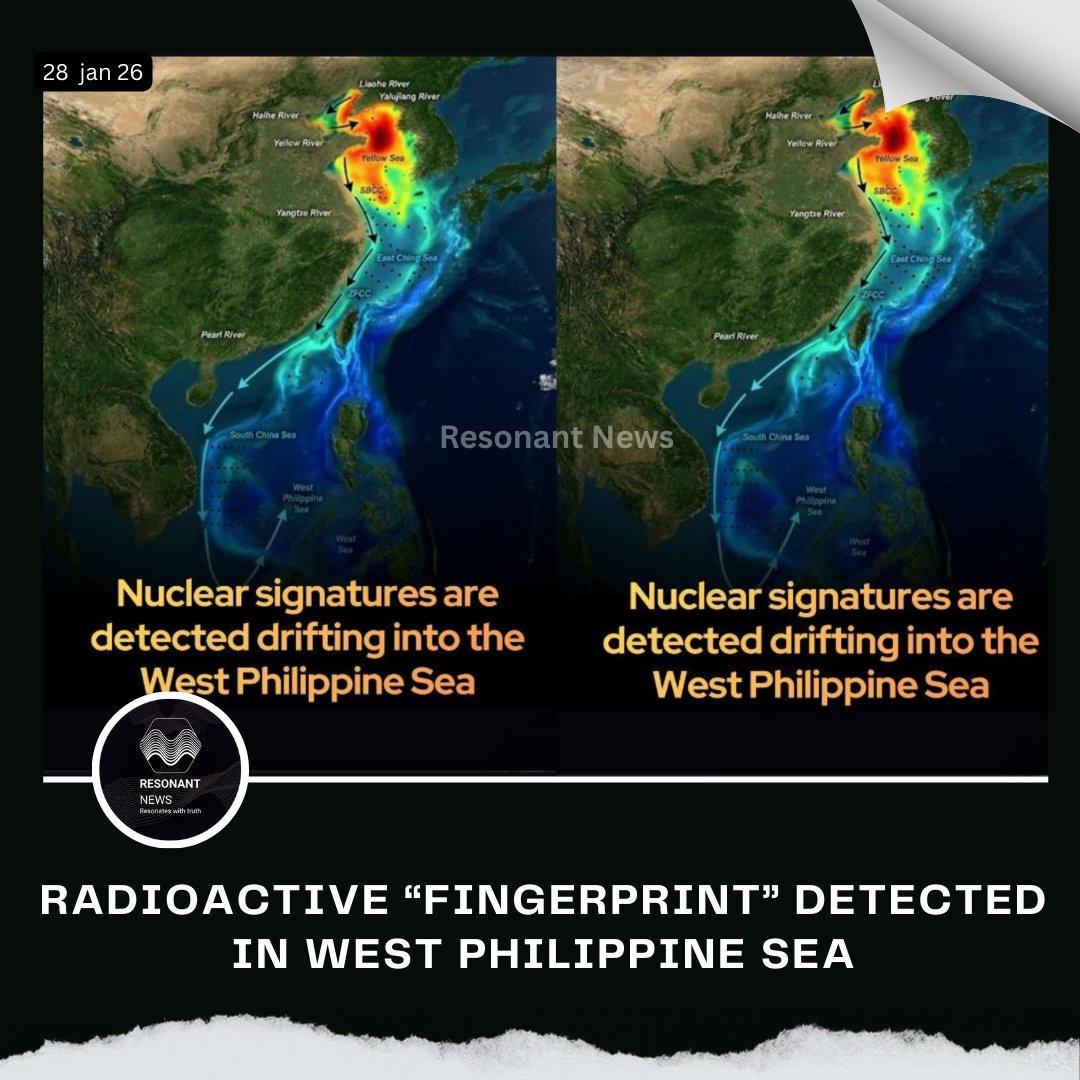

The study traces the likely pathway of this isotope to the Bohai Sea and Yellow Sea regions north of the Philippines. Researchers propose that ¹²⁹I originated from a combination of historical sources, including past nuclear weapons tests (such as those at China’s Lop Nor site and the former Soviet Semipalatinsk test site), nuclear fuel reprocessing facilities (potentially including European releases that affected northeastern China), and the 1986 Chernobyl accident. These contaminants likely deposited onto soils in northeastern China, were washed into rivers, entered the Bohai and Yellow Seas, and were then transported southward by ocean currents—such as the Yellow Sea Coastal Current and Chinese Coastal Current—into the South China Sea and ultimately the West Philippine Sea.

Experts emphasize that the detected concentrations remain extremely low and pose no immediate threat to public health, marine ecosystems, fisheries, or human consumption of seafood. The levels are far below any harmful thresholds.

This discovery underscores the interconnected nature of the world’s oceans and the long-distance transport of even trace radioactive pollutants through complex circulation patterns. The findings highlight iodine-129’s value as a scientific tool for mapping ocean currents and water mass movements in the region.

The researchers call for enhanced regional policies on managing transboundary radioactivity to better monitor and address such phenomena in shared marine environments. The study demonstrates how collaborative international research can reveal hidden environmental dynamics in geopolitically sensitive waters.

Leave a Reply